In search of stability and peace in Haiti

The outgoing humanitarian coordinator for Haiti at the United Nations (UN), Ulrika Richardson, was reported on 12 August as describing the situation that she was leaving behind in Haiti as “strikingly horrific”. It would be hard to disagree with this assessment, and equally hard to be optimistic about the prospects for the latest international blueprint for Haiti’s future – a report titled ‘Towards a Haitian-led Roadmap for Stability and Peace’ published in August by the Organization of American States (OAS) – however essential the effort might be.

The proposed roadmap follows on from an OAS resolution adopted in June 2025 which called on the OAS secretary general to develop an action plan for Haiti within 45 days.

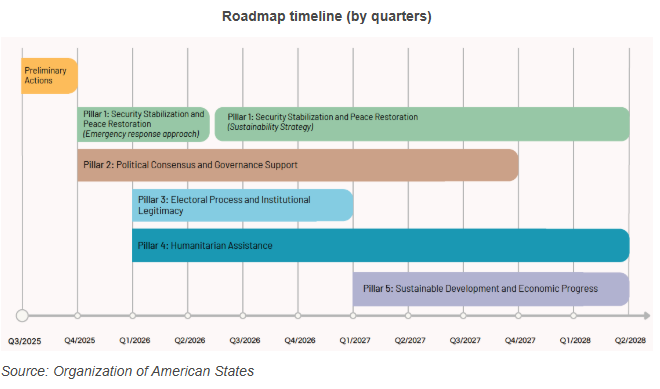

The plan has five ‘strategic pillars’, namely:

Security stabilisation

Political consensus

Electoral legitimacy

Humanitarian response

Sustainable development

Not surprisingly, the roadmap’s ‘security pillar’ is described as the highest priority. It is the foundation on which everything else depends. As the report highlights, armed gangs now control around 90% of the capital Port-au-Prince; over 5,600 people were killed by violence in 2024; 1.3m are displaced; 2m children are missing school, and 300 schools have been destroyed; only one-third of the population has consistent access to healthcare; 4.7m face food insecurity; and the unemployment rate is over 40%.

Talking in mid-August, William O’Neill, the UN’s designated expert on human rights for Haiti, said that the right to life, the right to bodily integrity, and the right to access food, healthcare, clean water, shelter, and education had “all been severely compromised”. But he also highlighted that gangs were not the only problem. Self-defence groups are themselves now behaving like the gangs they oppose. As O’Neill puts it: “If you’re a young man that they don’t recognise and have a tattoo or don’t have ID, they will kill the person on the spot and burn the body.”

A UN news report published on 1 August stated that in May this year, a self-defence group attacked the town of Petite-Rivière where they killed over 55 people for allegedly supporting a gang. The victims, mostly farmers, were attending a religious ceremony.

Some officials are also a problem, with the UN reporting in July that there were 19 extrajudicial executions by security forces in the departments of Artibonite and Centre between October 2024 and June 2025. Arbitrary killings were also flagged as a concern by the US State Department in its annual global report on human rights, published in August. The State Department report says: “Impunity remained a significant problem with the national police force. Civil society representatives alleged widespread misconduct among police officers driven largely by poor training and a lack of professionalism.”

The State Department report also highlighted the case of Jean-Ernest Muscadin, chief prosecutor in Nippes department. Between 1 April and 30 June 2025, Muscadin reportedly claimed responsibility for the killing of at least 27 alleged gang members.

Commenting on the case of Muscadin, UN human rights expert William O’Neill said: “Why is he popular? It’s because the institutions have failed. It’s this vicious cycle that as long as the institutions are still so weak, you have the Wild West like in old American movies, where the sheriff is the judge, jury and the executioner, all in one.”

Since March 2025, the gang violence has extended from the capital to areas such as Artibonite and Centre departments, and beyond central Haiti towards the border with the Dominican Republic. A July report by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) warned that “the expansion of gang territorial control poses a major risk of spreading violence and increasing transnational trafficking in arms and people.”

While Haiti’s national police (PNd’H) and the Kenya-led Multinational Security Support (MSS) mission, authorised by the UN, have launched many operations to retake territory from the gangs, successes have for the most part proved temporary. One of the problems is that the MSS has never been fully funded and supported. According to the OAS roadmap, only 40% of the intended 2,500 personnel have been deployed, “keeping operational capacity well below critical levels required for effective stabilisation”.

The security pillar

Having described the security pillar as having the “highest priority”, the OAS roadmap adds that there are two phases. The first is the short-term emergency phase which is to be focused on securing strategic assets, critical infrastructure, and the regaining of territory, and the second is making these gains sustainable and permanent through the rebuilding of “responsible and accountable security and justice systems”.

Under the OAS proposals, the MSS mission remains the lead entity for the emergency phase, with its main role being to provide operational support for the PNd’H but with the OAS in turn providing logistical and operational support to the MSS.

The list of 22 action points for the security pillar outlined in the OAS roadmap gives a sense of how ambitious the plan is. They include rebuilding the PNd’H by prioritising recruitment, training, and equipping of new police officers; disrupting the finances of organised crime through support for Haitian-led investigative and judicial processes; building the rule of law and judicial capacity; preventing gang violence and youth recruitment; and providing specialised training in investigation, evidence handling, and anti-trafficking measures.

With regard to the timeframe, OAS Secretary General Albert Ramdin said that “we hope that after 36 months we could have a situation where security is reasonably under control”. At present the mandate for the MSS mission expires in October. There is speculation over whether the MSS will be bolstered by a new security contingent, after US representative to the UN Dorothy Shea announced that the US and Panama are drafting a resolution to establish a new 5,500-strong, UN-backed, ‘Gang Suppression Force’.

According to the OAS roadmap, the estimated cost of the security pillar is US$1.33bn, however that is for 2,500 MSS personnel, not for the 5,500 now proposed by the US.

Political consensus

There have been no elections since former president Jovenel Moïse (2016-2021) was elected president in 2016. Following his assassination, former prime minister Ariel Henry (2021-2024) held power for three years until his resignation in April 2024 amid significant unrest, since when Haiti has been ruled by a Transitional Presidential Council (CPT) which is intended to hand over power to a newly elected president in February 2026. The ‘Political Consensus and Governance Support’ pillar of the OAS roadmap outlines seven steps to rebuild political consensus, including exploratory dialogue and the drafting of a new constitution, and it allocates US$8m for this.

Electoral process

The third pillar is described as “rebuilding a credible and trusted democratic pathway”. Its core objective is “to ensure that future Haitian leadership is genuinely chosen by the people through transparent, inclusive, and free and fair elections with international observation”. Another key objective is defined as establishing clarity regarding the sequence and scope of elections.

Among the 17 action points listed for this pillar is the need to “regulate candidate nomination”. It remains unsaid, but this would appear to be the most difficult objective of all. It is one thing to organise a smooth and transparent electoral process, it is another altogether to ensure that people of the right calibre, and untainted by the violence and corruption of the past, come forward to take up the challenge. The roadmap allocates US$104.1m to this pillar.

Humanitarian response

The humanitarian crisis in Haiti brought about by gang violence and the lack of government control has been compounded since January by the suspension of humanitarian aid from the United States.

On 30 July UN News published an interview with Modibo Traoré of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (Ocha) in which he said that President Donald Trump’s January 2025 executive order imposing a suspension of all new foreign funding by US federal agencies led to the sudden halt of 80% of US-funded programmes in Haiti.

Traoré said: “The year 2025 marks a turning point in humanitarian aid in Haiti…The interruption of US programmes has acted as a catalyst for the crisis. USAID’s technical partners, many of whom managed community health programmes in vulnerable neighbourhoods, have ceased operations, depriving hundreds of thousands of people of vital services.”

He added: “Children are among the hardest hit. Unicef [the UN Children’s Fund] and its partners have treated more than 4,600 children suffering from severe acute malnutrition, representing only 3.6% of the 129,000 children expected to need treatment this year.” The proportion of institutional maternal deaths has also increased from 250 to 350 per 100,000 live births between February 2022 and April 2025.

The OAS roadmap seeks to rectify these deficiencies with the delivery of life-saving aid in food, water, health, education, and shelter valued at US$908.2m.

Sustainable development

The final pillar of the OAS Roadmap relates to sustainable development and economic progress, with a strong emphasis on agriculture and rural development, partnering with the Inter-American Development Bank Group (IDBG), the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA), the Pan-American Health Organisation (Paho), the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB), and the UN’s Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (Eclac).

Among the ambitious ‘lines of action’ for this pillar are the need to develop human capital by investing in “quality education, healthcare, and vocational training” to improve the productivity of the workforce and to “enhance the overall human capital index”.

Other lines of action include improving the business environment through support for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), improving contract enforcement, and developing reliable infrastructure. The estimated cost for this pillar is US$256.1m.

US reactions

Following the publication of the OAS roadmap, the US mission to the OAS published remarks on 20 August welcoming “the urgency with which this roadmap was developed” and thanking the OAS for its “diligent work”.

The statement then went on to add that the US, alongside Panama, would seek authorisation for a UN Support Office to back up and resource the MSS mission. It added: “The next international force must be resourced to hold territory, secure infrastructure, and complement the Haitian national police.” And it said: “We note that the security pillar remains underfunded. We must be clear-eyed on the need to ensure a fully operational HNP [national police force] is in place that is sufficiently equipped to fill the vacuum that international forces will leave once they depart Haiti...A clear resource mobilisation strategy is essential, with prioritisation if funding falls short.”

The US statement ended by giving full backing to the OAS as the lead actor, saying: “We underscore the strengthened role of the OAS – not as one actor among many, but as facilitator, convener, and coordinator of hemispheric support.”

Finally, the US statement warned that the OAS cannot afford “phased planning” in the face of Haiti’s “existential crisis”. It said “mission-critical needs must be prioritised immediately, while medium- and long-term measures are layered in as conditions allow”.